There has been a lot of interest in data collected about users by Facebook recently. Journalists have been shocked when they downloaded the data that Facebook has on them. Most of this concern has been focused around data collected through explicit user interaction such as web browsing, or clicking on “Like” and “Share” buttons.

Background data collection, which occurs without any explicit user intervention, is arguably creepier, because it collects data whether or not you interact with the service. For example, Facebook has been criticized for logging texts and phone calls in the background. Facebook argues that users consented to sharing the data, although many users are still skeptical about how explicit the consent was. Similarly, Uber had to backtrack when it was discovered that it tracked user location automatically, even after the Uber trip ended .

However, in both these cases, there is clarity about data ownership boundaries. Facebook and Uber are separate apps that people have to explicitly install, and are clearly not part of the software that the phone arrives with. They don’t provide core functionality that other apps depend on, and uninstalling or disabling them does not affect phone functionality. Google, however, owns android, so the data collection boundaries and terms of consent are fuzzier. In this blog post, I look at this blurry boundary in the context of location tracking on android, and raise some questions around consent, transparency and competition.

I want to clarify that I am not opposed to Google, or to background location tracking in principle. My personal phone is an Android (although my next one might not be), and my PhD thesis is on building an open-source mobilityscope (https://e-mission.eecs.berkeley.edu/). I chose this topic because I believe that if used properly, such trip diaries can have many positive impacts on the way we design cities. But I also think that tracking people without their consent and without proper controls in place is creepy and wrong, and judging from the furor about social media data collection, a lot of people agree. I hope this blog post contributes to the ongoing privacy discussion by broadening the domain from web search and social media to automatic collection of privacy-sensitive data. It also raises questions about the complex relationship between competition, transparency and control when the data collection infrastructure is proprietary.

The prompt

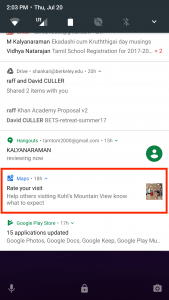

This story starts when I was shopping at Kohl’s last July and I got a prompt from Google maps asking me to “Rate my visit”.

- Prompt to rate Kohl’s

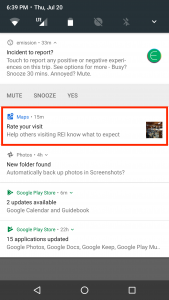

- Prompt to rate REI

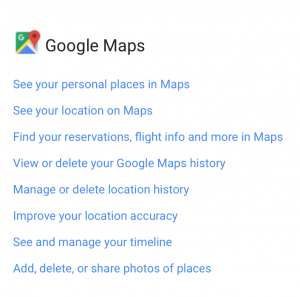

The consent

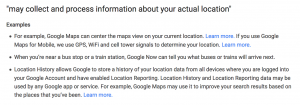

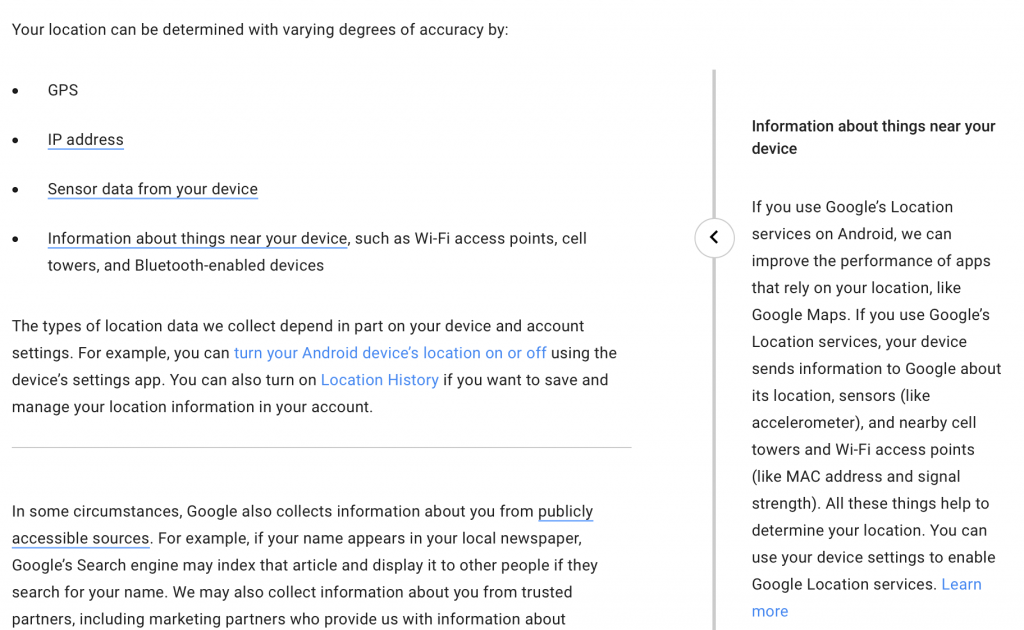

My PhD topic is on building an open-source mobilityscope, and I have thought a lot about background location tracking and related consent issues. So my curiosity was piqued – I had Google Location History turned off, and the other examples on Google’s Privacy Policy appeared to only cover location tracking while using Google Maps. I clearly wasn’t using Google Maps to navigate the racks at Kohl’s, and I hadn’t even used it to get there. So how did Google Maps know where I was? I snapped a quick screenshot so that I could look into it later.

- Location privacy policy

- Examples of how it is used

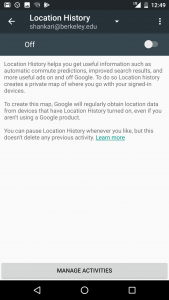

The controls

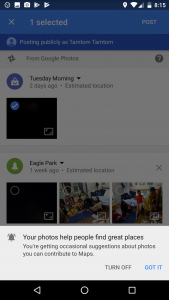

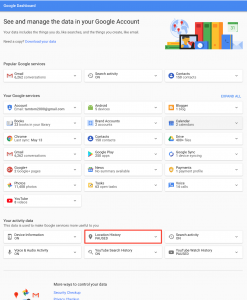

As the year went by, I would periodically get similar prompts from Google Maps – sometimes to rate a place, sometimes to contribute photos. The prompts were not consistent – they would only intermittently show up, even on multiple visits to the same store at around the same time of day. There were no obvious controls for either the tracking or the algorithm to generate prompts. The default option was to turn the prompts, not the tracking off. I would snap screenshots periodically, but since Google is closed source, I was no closer to being able to control how Google Maps knew my location all the time.

- Controls for prompts but not tracking

- in the online dashboard too

- except for location history, which is off

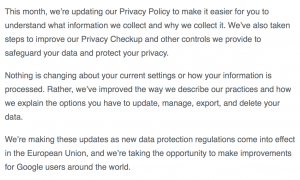

The update

Then, this week, I got an email from Google about an update to their Privacy Policy. The privacy policy takes effect on May 25, and is related to the new GDPR regulations. I was curious to see whether they had made any changes in location tracking and they had. And the changes seem to answer some of my questions and raise a host of others.

- GDPR-prompted policy update

The speculation

The story so far is fact, and backed up at every step with screenshots. At this point, since Google is unlikely to suddenly open source Maps, I must resort to speculation. Given the changes to the privacy policy and my experiences with background data collection so far, I think that the speculation is reasonable. If you have alternate explanations, please add them to the comments!

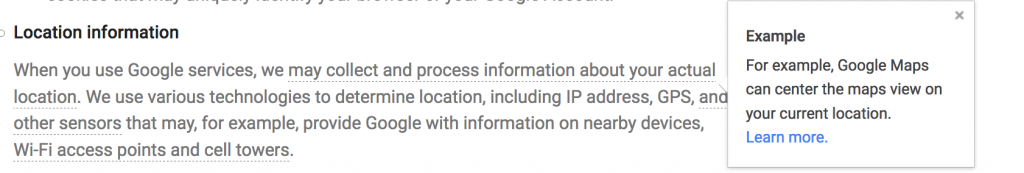

- Location privacy policy

- New location privacy policy

As you can see, the main change is to specify that using Google Location Services can be used to “improve the performance of apps … like Google Maps”.

Google Location services (earlier called Google Play services) is distinct from the open source Android Location services that provides direct access to various sensors. It is a closed source, uninstallable system service that fuses data from multiple sources to determine location. The key component of such a service is a database that maps location from high-power sensors such as GPS to the signature of low-power sensors (such as WiFi and cell towers). The location can then be determined by using WiFi and cell tower connections that are used for phone operation anyway to lookup the actual location. Phone Operating Systems typically crowdsource this database by sending (GPS <-> signal strength) mappings from phones. Note that the database entries do not need place photos or ratings, and do not need to be associated with a particular user.

My speculation is that Google Location Services shares the location data that it collects for crowdsourcing with Google Maps, which which in turn prompts users for data that cannot be automatically sensed in the background, such as perceptions and photos. There does not appear to be a way to turn off this sharing, even in the new privacy policy and controls. The only recourse is to turn off Google Location Services entirely, which impacts not just the Google Maps app, but the entire phone functionality.

The questions

In my mind, this update to the Privacy Policy raises more questions than it answers:

-

- When did I agree to this? The new privacy policy is supposed to take effect May 25, to coincide with the GDPR. But I have been seeing these prompts for almost a year, since July 2017. And as we have seen, the previous privacy policy did not give any examples of background data collection, or clarify how to control this tracking. And even the current privacy policy does not give any instructions on how to turn off the sharing between Google Location Services and Google Maps.

- Location history turned off, no other maps controls in the dashboard

- How does Maps get the location? The data is either sent locally or remotely and both options seem problematic for various reasons.

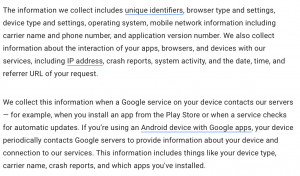

- If the location is sent locally, it could be sent through a standard location tracking API or a private API.

- Sending it through standard location tracking is equivalent to Google Maps requesting periodic location updates just like any other third party app. In that case, where is the data collection policy and control to turn this additional tracking on and off? Note that Location History is already paused in the dashboard, and there do not appear to be any other settings for Maps.

- Sending it through a private API seems to give Google Maps an unfair advantage over other location based services such as Yelp or Foursquare.

- If it is sent remotely, possibly by generating a push notification from updates received by the signal strength database, the data collection cannot be anonymous. This is because the push notification needs to know which device to send the notification to. In this case, why isn’t the non-anonymized data available in the dashboard for review and deletion?

- If the location is sent locally, it could be sent through a standard location tracking API or a private API.

- How does Maps convert the location to a business name? This raises a set of similar questions.

-

-

- If Maps receives the location locally and then queries a server to retrieve the business name, then the API call to retrieve the location is logged on the web server, along with, at a minimum, the requesting IP. If a user then makes a query at that location from their logged-in android phone, for example, to look up prices at a competing store, then it is possible to infer the location that the query was made from. So the location data is no longer anonymized.

- Information logged when apps retrieve data

- If Maps receives the location remotely and the business name is looked up before sending the location, the location query won’t be logged, but again, the device will need to be identified so that the push notification can be sent to it, so the location collection is no longer anonymized.

-

-

To recap, data collection for web browsing and social media is currently under intense scrutiny, but smartphone sensors can be the source of even more privacy sensitive data, collected completely without human interaction. Issues around consent, control and trust are currently fuzzy in this domain due to the blurring of boundaries between the phone operating system (OS) and proprietary services. How do you think we can re-establish some boundaries and provide greater clarity to users? How can we truly know what closed source software is actually collecting and when it is doing so? Please add your thoughts to the comments below!

Comments 3

Pingback: AP Exclusive: Google tracks your movements, like it or not - KYMA

Pingback: A Step by Step Guide to Use Google Map for Route Planning - UpperInc

Pingback: A Step by Step Guide on Google Maps Route Planner - UpperInc